Brazil is experiencing a huge outbreak of dengue, the sometimes deadly mosquito-borne disease, and public health experts say it is a harbinger of a coming surge in cases in the Americas, including Puerto Rico.

Brazil’s Ministry of Health warns that it expects more than 4.2 million cases this year, exceeding the 4.1 million cases that the Pan American Health Organization recorded for the 42 countries in the region last year.

Brazil was expected to have a bad year for dengue (the number of cases of the virus generally rises and falls in a cycle of about four years), but experts say a number of factors, including El Niño and climate change, have significantly amplified the problem this year.

“The record heat in the country and the above-average rainfall since last year, even before the summer, have increased the number of mosquito breeding sites in Brazil, even in regions that had few cases of the disease,” said the minister. of Health of Brazil, Nísia. Trindade, she said.

The number of dengue cases has already skyrocketed in Argentina, Uruguay and Paraguay in recent months during the southern hemisphere summer, and the virus will move up the continents with the seasons.

“When we see waves in one country, we will generally see waves in other countries, that’s how interconnected we are,” said Dr. Albert Ko, a dengue expert in Brazil and a professor of public health at Yale University.

World Health Organization has warned that dengue is rapidly becoming an urgent global health issue, with a record number of cases last year and outbreaks in places, like France, that have historically never reported the disease.

In the United States, Dr. Gabriela Paz-Bailey, chief of the dengue section of the division of vector-borne diseases at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said she expected high rates of dengue infection. in Puerto Rico this year and that there would also be more cases in the continental United States, especially in Florida, as well as in Texas, Arizona and southern California.

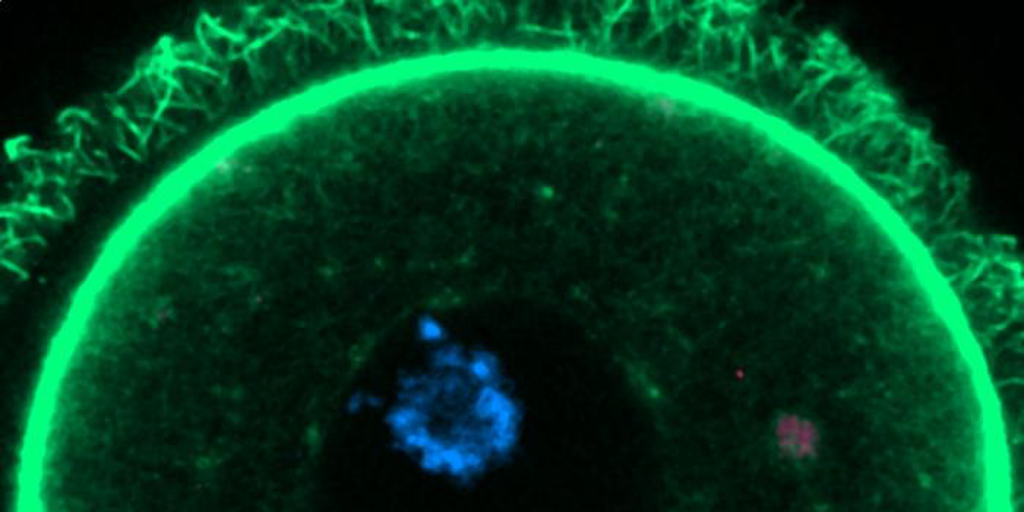

Dengue is transmitted by Aedes aegypti, a species of mosquito that is establishing itself in new regions, including warmer, wetter parts of the United States, where it had never been seen until recent years.

Cases in the United States are still expected to be relatively few this year (hundreds, not millions) due to the prevalence of air conditioning and window screens. But Dr. Paz-Bailey warned: “When you look at the trends in the number of cases in the Americas, it is scary. “It has been increasing steadily.”

Florida reported its highest number of locally acquired cases last year, 168, and California reported its first such cases.

Three-quarters of people infected with dengue do not have any symptoms, and among those who do, most cases will resemble only a mild flu. But some dengue infections are serious, causing headaches, vomiting, high fever and joint pain that gives the disease the nickname “breakbone fever.” A severe case of dengue can leave a person weakened for weeks.

And about 5 percent of people who get sick will progress to what is called severe dengue, which causes plasma, the protein-rich liquid component of blood, to leak from blood vessels. Some patients may go into shock, causing organ failure..

Severe dengue has a mortality rate of between 2 and 5 percent in people whose symptoms are treated with blood transfusions and intravenous fluids. However, when untreated, the mortality rate is 15 percent.

In Brazil, state governments are creating emergency centers to test and treat people for dengue. The city of Rio de Janeiro declared a public health emergency over dengue on Monday, days before the start of the annual Carnival celebration, which draws tens of thousands of people to outdoor parties during the day and night.

Large numbers of cases are being reported in Brazil’s southernmost states, said Ms. Trindade, the health minister, which are generally much colder than Rio and the central and northern states. People in those areas will have little immunity to the disease due to previous exposure.

Dengue occurs in four different serotypes, which are like cousin viruses. Previous infection with one offers only short-term protection against infection with another, and a person who has had one dengue serotype in the past is at increased risk of developing severe dengue from infection with another serotype.

“There are serotypes circulating in Brazil right now that have not circulated in 20 years,” said Dr. Ernesto Marques, associate professor of infectious diseases and microbiology at the University of Pittsburgh.

Brazil has started an emergency campaign to immunize children in areas with higher rates or risk of dengue transmission, using a two-dose vaccine called Qdenga that is manufactured by Japan’s Takeda Pharmaceutical Company. Brazil purchased 5.2 million doses for delivery this year, plus nine million more for delivery in 2025, and the company donated an additional 1.3 million, effectively blocking most of Qdenga’s supply globally. A company spokeswoman said Takeda is working on a plan to increase supply, focusing on delivery to countries with high prevalence.

But still, that’s enough to cover less than 10 percent of the Brazilian population in two years. The only good news about dengue in Brazil at the moment is the publication of the results of clinical trials of a new vaccine tested by the public health research center Butantan Institute in São Paulo. That vaccine requires only one injection, and the trial found that it protected 80 percent of those vaccinated against developing dengue virus disease. The research center will ask the Brazilian government for approval of the vaccine and has facilities to produce it, with the goal of beginning to administer injections in 2025.

For this outbreak, it is too late for vaccination to help much and public health authorities have few other ways to slow it down.

“Insecticide resistance really limits what can be done in terms of controlling the mosquito population, and insecticide resistance is widespread,” said the CDC’s Dr. Paz-Bailey. “What can be done is to ensure that people have access to clinical treatment and that doctors know what to do.”

Medical centers in Brazil are setting up extra beds for people with severe dengue, hoping to avoid the kind of overloading of health systems that occurred during the Covid-19 pandemic and prevent dengue deaths.

“The old paradigm that dengue affects children more is not the case in Brazil; you have to think about the elderly, who are very vulnerable,” said Dr. Ko. It will be important for both doctors and the public to understand the message of testing for dengue at the first sign of symptoms in both children and older people, he said.

“Any educated assumption was that this would be a bad year,” Dr. Marques said, “but now we know how bad it will be. “It’s going to be very, very bad.”

Lis Moriconi contributed reporting from Rio de Janeiro.